Matcha’s Unique and Ancient History

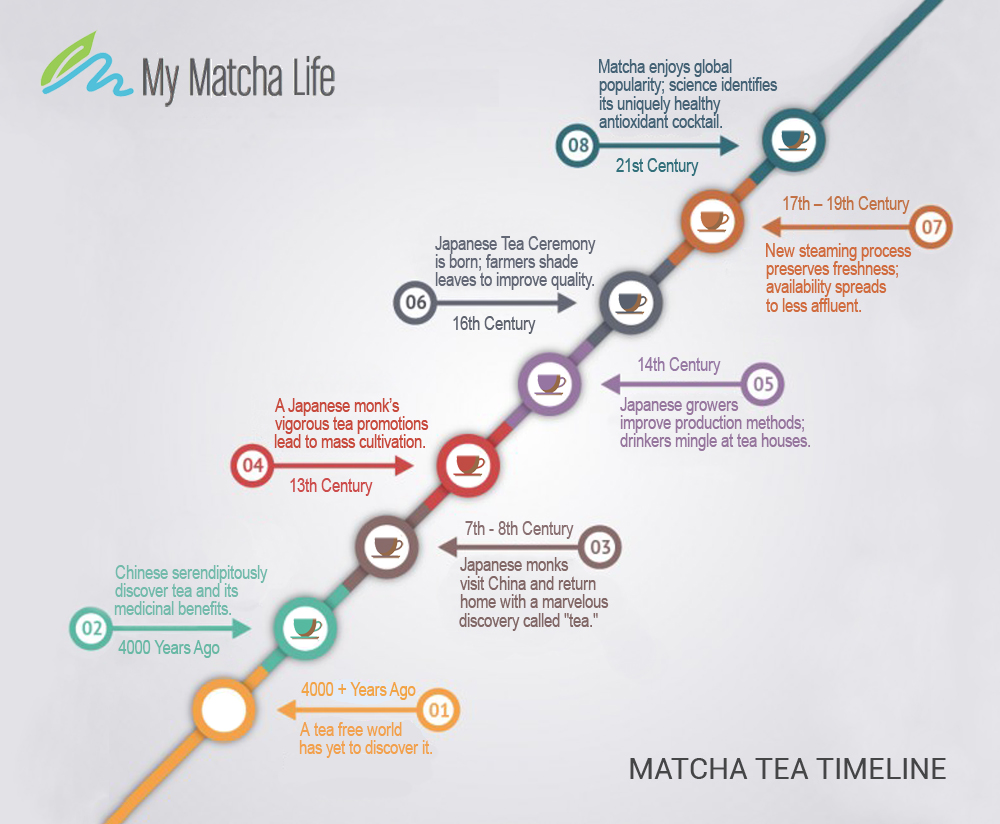

Matcha history is a journey of over 4,000 very eventful years. From the beginning, Chinese enthusiasts used tea to relieve inflammation, fever, anxiety and a host of other maladies. Ancient texts describe the legendary Chinese leader and health practitioner, Sheng Nong, who is credited with actually discovering tea as a beverage.

The legend contends that, one day, Sheng Nong experienced a profound sense of well-being after drinking hot water from an open pot into which tea leaves had blown from a nearby tree. He was so impressed he added ‘tea’ to his list of prized medicinal herbs.

Early on the Chinese developed a method by which tea leaves, baked and molded into convenient cakes, could be easily stored and transported. At tea time, a small piece of tea-cake would be broken off, pummeled into powder and whipped with a bamboo whisk in hot water. This ancient aspect of Matcha history accurately foreshadowed its modern incarnation.

7th – 9th Century

Japanese monks visiting China to study Zen Buddhism returned home with their discovery of tea’s wonderful health and healing properties during the 7th to 9th centuries. To their secluded monasteries they brought tea-cakes and seeds and quickly adopted the Chinese traditions of molded tea-cakes and hot water whisking. Tea provided the monks a healthy countenance, immediate energy and a mental focus that enhanced their meditations. At times, garlic and salt were added, creating what was considered an elixir of good health. The first recorded tea farms were established around monasteries in the Uji region of Japan — a region vital to Matcha history as the eventual birthplace of Matcha tea. For the next few centuries travel between China and Japan declined due in part to the insular nature of Chinese leaders during the period.

13th Century

It wasn’t until the early 13th century, some 400 years after its introduction to the island, that the monks’ discovery finally gained greater recognition in Japan. In 1211, monk Myōan Eisai famously wrote Kissa Yōjōki (Tea Good for Health), the book in which he proclaims tea nature’s ultimate mental and medical remedy to “conquer the five diseases” and “remedy all disorders.” 1 As a result, Eisai is credited with motivating the mass cultivation and consumption of tea in Japan. By the end of the 13th Century the Chinese had replaced tea-cakes with steamed tea leaves in a cup. It was this evolution they introduced to visiting Europeans instead of the ancient tea-cake traditions. Japanese monks, meanwhile, continued to process the rich powder that was to become the Matcha tea we know and love today.

14th – 15th Century

With the arrival of the 14th Century, tea growers in Japan were busy grinding their product beneath slabs of granite, creating both a finer green tea powder as well as new production efficiencies. This period is also noteworthy in Matcha history for its “Tocha Tea Tournaments” held in smallish two-storey buildings. The events — a curious blend of Buddhism, tea and competition 2 — featured blindfolded tea-tasting contestants attempting to identify gardens of origin while onlookers placed bets on who would win. The tournaments were eventually outlawed and the buildings turned into tea-houses of contemplation which would later invoke the more reverent activities of the Japanese Tea Ceremony.

16th Century

The 16th Century is instrumental in the evolution of today’s Matcha history in that it heralded the beginnings of the renowned Japanese Tea Ceremony called Chado or Sado which means “The Art of Tea.” Zen Buddhist monk Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591) would become known as the patriarch or father of the much celebrated ceremony. It was during this period tea farmers realized that shaded tea leaves produced a more refined taste. As such, the practice of covering sprouted tea plants with bamboo and rice straw shades (Tana) was adopted. Because powdered Matcha was still being processed in relatively small quantities it was, at the time, typically reserved for royalty, samurai, priests and wealthy merchants.

17th – 19th Century

As new cultivation and processing practices evolved, Matcha tea found eager new devotees among the general Japanese populace. This was especially true during the Edo Epoch (1603-1867). This period in Matcha history also saw Japanese producers adopt a revolutionary new processing method in which tea leaves were steamed to help preserve their rich color and medicinal benefits. Steaming meant everyone, not just the ruling elite, could now enjoy the natural goodness of this healthier “green tea.” Until then, most locals had contented themselves with roasted brown Bancha tea leaves.

20th – 21st Century

The wide cultural adoption of daily tea times and the appearance of new varietals heralded what has become the modern era of Japanese tea. It began late in Matcha history, just 250 years ago, when everyday citizens finally shared in the mind and body benefits of regular green tea consumption. It continues today, worldwide, as we witness an emerging Matcha renaissance and a new appreciation of some centuries-old secrets.

References

1) The Story of Tea by Mary Lou Heiss (pp. 165 – 166)

2) The Tea Industry by Nick Hall (pp. 6 – 7)